Kim Philby Read online

CONTENTS

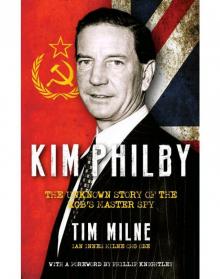

Title Page

Epigraph

Foreword by Phillip Knightley

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Introduction

1. The Public Schoolboy

2. New Frontiers

3. Change of Life

4. Own Trumpet

5. Section V

6. On the Map

7. Ryder Street and Broadway

8. Decline and Fall

9. Over and Out

10. ‘The KGB Officer’

11. The Elite Force

12. Retrospect

Epilogue

Appendices

Index

Plates

Copyright

‘If in the end he still remains something of a mystery, we should not be surprised: for every human being is a mystery and nobody knows the truth about anybody else.’ – A. A. Milne

FOREWORD

This memoir is the previously unknown story of the long friendship between Kim Philby and Ian Innes ‘Tim’ Milne,1 an association which lasted for thirty-seven years, from the time they first met at Westminster School in September 1925 until Philby’s defection to Moscow in January 1963. It is the only first-hand account of the Philby affair ever written from the inside by someone who served in the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) and worked alongside the so-called KGB master spy. Philby’s own book was of course written in Moscow under KGB supervision and is therefore suspect.

From Westminster Milne and Philby proceeded to different universities – Philby to Trinity, Cambridge and Milne to Christ Church, Oxford – but they travelled together in central Europe during university holidays and remained close.

Philby joined SIS in September 1941. Milne followed him some weeks later, recruited by Philby as his deputy and serving alongside him in Section V for most of the war years. Like Philby, Milne stayed on in SIS after the war and they remained professional colleagues as well as friends until Philby’s dismissal from the service in 1951. Their friendship continued for a dozen years after this until Philby’s flight from Beirut.

When the Philby story first broke and became a hot news item in 1967, largely as a result of a series of articles in the Sunday Times written by me and two colleagues which subsequently became a bestselling book,2 Tim Milne was identified in print as being a close friend of Kim Philby, and although Milne was then still a serving officer in SIS, press interest in him became intense. I was working on the Insight team at the Sunday Times and the editor asked me to find Milne and try to persuade him to talk about his long association with Philby, particularly the holidays they had spent in Europe together. Was there a clue to be found there that explained Philby’s treachery? Milne politely sent me on my way, pleading the restrictions of the Official Secrets Act. He retired from SIS in October 1968, continuing in government service for another seven years, but he never spoke publicly on the subject of his friendship with Philby, although in later years he was invariably courteous to the various authors who approached him for information.

Tim Milne died at the age of ninety-seven in 2010 and his obituary in The Times3 stated in part that his ‘feelings on learning of his old friend’s sustained betrayal of his colleagues and his country can only be a matter of conjecture: he himself maintained great discretion on the subject for the rest of his life’. It was not widely known, outside his family and former service, that he had in fact written a very full and frank account of his association with Philby, nor that his memoir had been accepted for intended publication in 1979. However, before any such publication could happen, Milne was required to submit the manuscript to SIS and obtain their permission to publish, in view of the confidentiality obligations incumbent on him. In the event, permission was denied and Milne reluctantly had to abandon the project.

Free of these obligations today, Milne’s daughter has now given permission for her father’s memoir to be published, and this account of a friendship which lasted almost forty years and included a professional relationship for ten of those can now be related in full. Over the past forty-seven years, since the first articles on Philby were written, a considerable number of other articles, TV documentaries and drama treatments, as well as countless books, have appeared: none, however, have been written by someone who knew him as well, or for as long a period, as Tim Milne.

It comes as little surprise that this memoir is so elegantly and well written, given that Tim’s father, Kenneth John Milne, was a contributor to Punch magazine and a close literary collaborator with his brother (Tim’s uncle), Alan Alexander Milne, the author of the Winnie-the-Pooh books among others.4 Tim’s own inherited and natural writing excellence was also in demand after he left Oxford, as he worked for five years as a copywriter for a leading London advertising agency before war intervened.

Although Kim Philby’s treachery was to cause Milne personal distress and considerable professional difficulties, he writes about his long association with Philby without any hint of rancour or bitterness. When I interviewed Philby in Moscow in 1988, he told me, ‘I have always operated at two levels, a personal level and a political one. When the two have come into conflict I have had to put politics first. This conflict can be very painful. I don’t like deceiving people, especially friends, and contrary to what others think, I feel very badly about it.’5 Philby’s widow said in an interview in 2003, ‘To the end of his days he openly talked about how the hardest and most painful thing for him had been the fact that he had lied to his friends. Until the very end it is what tortured him most.’6

It is not known whether Milne knew of these statements, as undoubtedly he was one of the friends to whom Philby was referring. When the news came that Philby had died, in Moscow on 11 May 1988, Tim’s daughter asked, ‘I suppose you have mixed feelings?’ Milne replied, ‘No, for me he died many years ago.’

One recent author on the subject of Philby wrote, ‘Many individuals exert a fascination over the public, but rarely has one individual held such a fascination for so many years for a country that they betrayed.’7 The year 2013 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Philby’s defection to Russia and twenty-five years since his death in Moscow: following these anniversaries, the publication of Tim Milne’s full account of his close friendship and association with this most unusual man may now provide readers and historians alike with the closing chapter on the story of Kim Philby.

Phillip Knightley

January 2014

[Editor’s note: These notes were compiled (not by the author) some time after the book was written.]

Notes

1. From childhood and for the rest of his life, Milne was known to his family and friends as ‘Tim’.

2. Phillip Knightley, Bruce Page and David Leitch, Philby: The Spy Who Betrayed a Generation, André Deutsch, London, 1968.

3. A lengthy obituary was published in The Times on 8 April 2010.

4. For an excellent account of the life of A. A. Milne and the close relationship with Kenneth (who died in 1929) and Kenneth’s widow and children, see Anne Thwaite, A. A. Milne: His Life, Faber, London, 1990.

5. Phillip Knightley, Philby: The Life and Views of the KGB Masterspy, André Deutsch, London, 1988, p. 219.

6. Rufina Philby, interview with the Sunday Times, June 2003.

7. Gordon Corera, The Art of Betrayal: Life and Death in the British Secret Service, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2011, p. 92.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is dedicated to the memory of my parents. My father wrote his account in longhand, and my mother typed and retyped the manuscript many times. Though it is ostensibly my father’s book, in reality it was a joint project which involved them both for several years. I know how very pleased they would have been to see the publicat

ion of this memoir, even so long afterwards.

Most, if not all, of my father’s colleagues and contemporaries in SIS have now died, and Kim Philby himself died more than twenty-five years ago. However, this is one story which never seems to lose its fascination for many, despite the half-century which has passed since Philby’s defection to Russia.

The final version of my father’s manuscript was accepted for publication both in Britain and in America in 1979. I remember how disappointed and discouraged my father was when he was denied permission to publish. The manuscript was subsequently abandoned, and during his lifetime my father never revisited the possibility of publication.

Considerable thanks must now go to my collaborator, Richard Frost, who first encouraged me to proceed with this project, and then worked tirelessly on the editing and the source notes, before acting as intermediary between me and Biteback Publishing. Without Richard, it is certain that the typescript of this book would still be languishing in a ring binder, unseen.

I should also like to thank Phillip Knightley, who contacted me after my father’s death to enquire whether a manuscript still existed, and if so whether he could read it to express an opinion on its suitability for publication today. I am very pleased that he has contributed the foreword to the book.

Finally, I must warmly thank my editor, Michael Smith, for all his advice and friendly help, Hayden Peake for his expert guidance, and the excellent team at Biteback, not least the copy-editor Jonathan Wadman, who is himself an ‘Old Westminster’.

Catherine Milne

February 2014

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Images in the plate section are reproduced with kind permission of the following:

Page 1 top and bottom, page 2 bottom left and right, page 8 bottom left and right © Catherine Milne

Page 1 middle © Adelphi – The Latin Play, 1928. Reproduced with kind assistance of the Governing Body of Westminster School.

Page 6 top and page 7 top © Press Association

All other images are supplied from a private collection.

INTRODUCTION

Many books have appeared on Kim Philby, including the chief character’s own account.1 Much of the story has been laid bare. But from my long friendship with him I believed that, although I had no startling revelations to make, I could fill a few gaps in the published record and perhaps correct one or two misconceptions, as I saw them, and having now retired from government service I would like to contribute my recollections.

This is not a researched book. I have no documents or letters, and no access to unpublished material. It is many years since I had anything to do with intelligence work. I write from memory, jogged here and there by books and articles already published, though there must be many I have not read. On several points of wartime detail where my recollection differed from existing accounts I consulted former intelligence colleagues, long retired.

The original Sunday Times articles of 1967 published for the first time many of the basic facts about Philby’s career. Although these articles caused some publicity difficulties for me at the time, I thought the Sunday Times helped to establish a valuable point of principle, which I fully support: provided its current and future work is not seriously handicapped, a secret service has no right to permanent immunity from public scrutiny and criticism; it cannot expect that faults and errors should be hushed up indefinitely.

In my own book, the first nine chapters (excluding Chapter 4, which is largely autobiographical) describe chronologically my acquaintance with Kim Philby from our first meeting in 1925 to our last in 1961. I have tried as far as possible not to duplicate what others have written, but to rely on my personal recollections. However, there were several periods of his life of which I knew little at first hand, notably Cambridge, the Spanish Civil War, Washington and Beirut; to the small extent I have touched on these I have usually drawn on other accounts. But for the most part I have described things as I saw them at the time, with occasional passages of hindsight. The period 1941–45 and the Iberian subsection of Section V of the Secret Service, in which he and I worked, are treated in some detail. I have freely discussed wartime intelligence matters, as have many others; but post-war intelligence, for the most part, is mentioned only in passing. Chapter 12, without pretending to be a deep analysis of Kim Philby, man and spy, offers some thoughts on his motives and personality.

I do not agree with several writers who have stated that Philby was essentially an ordinary man in an extraordinary situation; rather, I would say, he was an unusual man who sought and found an unusual situation. Nor, from what I saw of Kim and St John Philby, do I believe the theory of the domineering or dominant father.

I have tried to avoid either condemning or condoning what Kim did. This is not because I have no strong views, but because I am trying to write a factual account of what I knew of him. It would only confuse things if I were to hold a moral indignation meeting every few paragraphs. If the personal picture I have presented is friendlier than several others that have appeared, well, that is how I saw him.

Tim Milne

Author’s note

The Soviet organisation which Philby joined in the 1930s had many titles before settling down in 1954 as the KGB. I have not attempted to follow these changes, which would merely confuse the reader, not to mention the author. Where the context requires, the term KGB should be considered to include its predecessors, and the term NKVD its successors; the intervening titles have not been used.

I have referred throughout to SIS, not MI6; and to MI5, not the Security Service.

Notes

1. Kim Philby, My Silent War, MacGibbon & Kee, London, 1968.

1

THE PUBLIC SCHOOLBOY

September, 1925. A very small boy is happily trying to squash a bigger boy behind a cupboard door. Another small boy, me, is watching with some alarm.

That is my first memory of Kim Philby. An hour earlier I had been deposited at 3 Little Dean’s Yard, one of the new batch of King’s Scholars at Westminster School. Kim, although only six months older than me and still diminutive in his Etons,1 was beginning his second year. The forty resident King’s Scholars formed a separate house, called College, which in some ways was a kind of school within a school, with its own traditions, rules, clothes and vocabulary. The juniors, as scholars in their first year were called, had a fortnight to master these mysteries. During this time each junior was assigned to the care of a second-year scholar, who not only would be his mentor but would take the rap for any sins committed by his protégé. My own mentor was now ignominiously pinned behind the cupboard door, and I wondered – unjustly as it turned out – what good he would be to me if he could not manage this small pugnacious fellow with a stammer.

Kim was the only person in College, and almost in the entire school, that I had heard of before. Over a period of about a decade at the turn of the century, my father and his brother Alan, and Kim’s father, St John Philby,2 and his father’s brother, had all been at Westminster, the first three in College. St John Philby had earlier been a pupil in the 1890s at a preparatory school of which my grandfather J. V. Milne was founder and headmaster. (In his autobiography,3 he says, ‘I cannot but feel that in J. V. Milne we enjoyed the guidance of one of the greatest educators of the period – certainly the greatest of all who crossed my path.’) The two families had been acquainted, but had drifted apart. I had never previously met any of the Philbys but my father had told me to look out for Jack Philby’s son.

Books and articles on Kim have made much of his public school background. Some accounts have implied that he was very much a product of the system and, that when suspicions of him arose, the system closed ranks and succeeded in protecting him for several years. In fact Westminster at this time, and particularly College, were not very typical of public school life, and Kim himself was highly untypical even of Westminster.

The school was not just in London, but in the very centre of London, closely linked with West

minster Abbey, which was our school chapel. (I must have attended between 1,200 and 1,500 services there in my time.) Two-thirds of the rather small complement of 360 pupils were day boys, and of the boarders (who included all the resident King’s Scholars) most lived in or near London; Kim’s house was in Acol Road, in West Hampstead. I myself, living in Somerset at the time, was one of the few boarders who could not go home at weekends. This was not a self-centred school, divorced from the outside world. It was also not one of the most successful schools, by the usual criteria of the time. We did not get many university scholarships, apart from our closed scholarships and exhibitions to Christ Church, Oxford and Trinity College, Cambridge. Unsurprisingly, with our small numbers and relative lack of playing fields on our doorstep, we were not too good at games. And socially we were not quite on a level with Eton, Harrow and one or two others.

But Westminster was an unusually humane and civilised place. There was room for a hundred flowers, if not to bloom, at least not to be trampled on. Eccentrics were prized, particularly if they made you laugh. In College, and perhaps in other houses, there was little or no bullying; the small boys tended to take advantage of this by taunting and tormenting the larger or older ones, as a puppy might an Alsatian. It was not a sin to be a dud at games, and there was in any case the alternative of the river; you can’t be a dud at rowing. In College, administration and discipline were mainly in the hands of the monitors, who had the power to cane juniors and second-year boys – usually for trivial offences. The fear of being caned was real enough in my first two years, but I was caned only once, and I’m not sure that it happened to Kim at all. There were many rules and restrictions, but once you reached your third year most of them ceased to apply.

Kim Philby

Kim Philby